They say that the eyes are a window to the soul, but there’s nothing like a financial windfall to provide a glimpse into our emotional undercurrents. The opportunity to invest new cash from a business sale, inheritance, or other source often makes even the most committed investor pull up short and ask, Is now really the best time to put more money into the market?

To help clients answer this question and avoid becoming paralyzed with their decisions, we used to emphasize the evidence -- for example, the data showing that from 1926 through 2019, you would have earned similar positive returns whether you’d invested after a new market high or after a market decline of at least 10%.

It’s a counterintuitive result, since we’ve all been taught to “buy low, sell high” to earn good returns. Yet the data shows that finding the perfect entry point for investing new cash is not nearly as important as most people think.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors1

We’d also point out that staying invested with old money is, effectively, the same thing as investing new money. There’s no law requiring you to stay invested in your diversified portfolio. Forgetting about taxes for a moment, you could liquidate the portfolio any day and combine the cash with your new money. So, if you’re willing to invest old money in the portfolio, why object to investing new money in the same way?

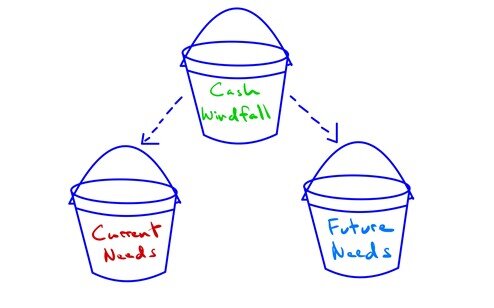

The real question is whether you want to use the new money sometime soon, for the you of today, or years from now for the you of tomorrow.

Current needs might include cash for this year’s living expenses, emergency reserves, or a new car. Future needs might include college funding or retirement years from now. Cash works best for current needs, since it doesn’t fluctuate. A diversified portfolio works better for long-term needs, since it can hedge against inflation.

If you intend to use your windfall for future needs, but are unwilling to invest it, then you’re choosing to change your portfolio allocation. In particular, you’re deciding to “dilute” your stock positions with a lump sum of cash, changing, for example, your 60% stock portfolio to 40% stocks. In theory, there’s nothing wrong with this, but you should consider the implications for your financial goals.

All this logic and evidence was well and good, but it didn’t help most clients move any closer to a decision for their new cash. Often, after we’d waxed eloquent about the proper framework for thinking about the windfall, the clients would say, “We’ll sit with it.”

To the extent this meant that they would reflect on their goals and how they might best use the new money, it was a positive. But often what they meant was, “We’ll sit on our cash until it becomes clear that it’s safe to invest.” Which could be months, even years later, potentially causing them to miss out on important opportunities in the meantime.

We’d feel bad, as if we’d failed them despite all the great analytical tools and experience we’d brought to bear on the issue. Eventually we wised up. The problem was that logic, evidence, and proper frameworks do not address the crux of the matter with a windfall: feelings about the new money.

These feelings vary from person to person, which is why personal finance is more “personal” than “finance.” However, one of the peculiarities common to many of us is that we feel differently about money, depending on the source from which it’s derived.

As finance professor Meir Statman points out in an interesting Wall Street Journal article this week, A Dollar Is a Dollar Is a Dollar. Except in Our Minds:

We regularly distinguish money earned with much effort, such as salary, from windfall money obtained with little or no effort, such as gifts. We tend to place hard-earned money in one mental pot and windfall money in another, and we spend windfall money more easily than we spend hard-earned money.

For some people, this may mean they feel more of a need to hold onto the windfall money rather than put it at risk in the market. Perhaps it feels like a one-time opportunity to get ahead. Or perhaps, if it’s a gift or inheritance, it comes attached to strong feelings or family ideals regarding how it should be used or preserved.

Whatever the reason, the stakes often feel higher with windfalls, and the thought of investing further in a diversified portfolio can feel like potentially throwing freshly printed hundred-dollar bills into a furnace. Clearly no amount of data and logic can help with this, particularly since, at the end of the day, we can’t know what comes next in the markets.

Instead, it’s often more helpful to address the feelings associated with the new money:

Listen to Your Hesitations

Maybe there’s a good reason you’re not comfortable investing it just yet, apart from what the markets are doing.

Your financial goals may have changed, or perhaps you recognize intuitively that your current investment approach is too risky, particularly now that you have extra resources to fund your goals.

Re-evaluating your approach and looking at the impact of the new money in the context of your other resources, within the context of your financial plan, may help you move forward with any investment.

Consider Other Uses For The Money

It’s not an all-or-nothing proposition, since you don’t have to invest all the new money. Paying down a mortgage or other debt can be a permanent victory no matter what the markets do next. Similarly, treating yourself to long-deferred gratification can help you feel more indifferent to market fluctuations.

Aim for a Good, Rather Than a Perfect Result

If last year taught us anything, it’s that there are no reliable market metrics or economic indicators that will let us know the perfect time to invest. Waiting for the perfect entry point likely means sitting on the sidelines with cash while the markets continue to rise.

If you have a sound, diversified investment strategy and enough time to accept the risks of investing for the long term, you might as well get started now.

Manage for Remorse

Once you’ve decided to invest some or all of your new cash, you have a choice: to invest the lump sum all at once or gradually over time. The evidence says that plunging into your diversified portfolio will tilt the odds in favor of better investment returns than wading in gradually with, say, monthly installments.

However, none of those odds matter if you’ll be prone to yank your money back out of the market should it fall right after you invest or feel terrible about the result. If you feel like you may be prone to that, focus on managing for remorse and go in gradually with your new money.

After all, one of the great ironies about successful investing is that it rests more on knowing yourself and managing for that than knowing what the market will do next.

1 This chart reports the performance of markets subsequent to new market highs and to declines of 10%. Declines are defined as months in which the market is below the previous market high by at least 10%. New market highs are defined as months in which the market is above all previous levels for the sample period. Results are shown for US large caps over one-, three-, and five-year annualized periods. Annualized compound returns are computed for the relevant investment periods after each decline or market high observed and averaged across all declines or market highs.