Given the jarring surprises of the past few years, it might seem risky to make any plans beyond next week. Why expose ourselves to more uncertainty and disappointment? However, thinking of our plans as blueprints and judging them by how close they adhere to the original design likely means they lack a critical ingredient.

This past summer, while isolating in a Milan hotel room, my vacation disrupted by a mild case of Covid, I discovered a cable t.v. show broadcast in Italy as “Lagoon Masters.” Each episode followed swimming-pool designer Lucas Congdon and his loyal crew from one Florida residence to another as they built the kind of waterfalls, rivers, and tropical gardens typically found at luxury resorts.

It wouldn’t have been much of a story if the projects had gone straight from blueprint to creation, but as it happened, each project seemed nearly to fall apart in its own particular way. Botched designs, equipment failures, and multi-ton rock slabs breaking in two just as they were lowered into place underscored the poet’s observation that “the best laid plans of mice and men often go awry."

Where other people would have thrown up their hands, Congdon seemed to relish having another cool problem to solve. By the end of each episode the homeowners got their lagoon, but he seemed to get something even better: an adventure. His whole life, in fact, seems to have been one long adventure - from growing up in a Vermont family of stonecutters and landscapers, to studying landscape design at Montana State, to dropping out of school to scout locations across the country for the best place to launch his firm.

There seems to be no way that Congdon could have planned the path that unfolded. However, in addition to becoming a landscaper at 14, he was a “self-described videophile” who’d been posting videos of his pool creations on YouTube for nearly a decade before the show ran. “I was hoping someone would discover me online someday.”

The theme running through Lagoon Masters and Congdon’s life is “trial and error.” As every contractor knows, there was simply no way to anticipate all the surprises and obstacles his team would encounter on each job. They had to get started, see what they bumped into, and figure it out from there.

Trial and error seems the opposite of planning. Plans are about thinking, trial and error about action. Plans try to imagine challenges in advance to avoid them; trial and error relies on improvisation once obstacles appear. Plans are for nerds with books and computers; trial and error is for superheroes.

It’s a false dichotomy. As Star Trek fans know, logic and planning (Spock) go hand-in-hand with action and improvisation (Captain Kirk) to create a far more powerful approach to problem-solving than either approach can offer alone. They are complementary forces, and the best plans, whether military, corporate, or personal, rely on both to navigate uncertain, real-world conditions.

Lagoon Masters was the perfect illustration of this: the blueprints gave Congdon and his crew the instructions that they needed to get started, and they often pulled out the schematics to help inform decisions about the problems that were lying at their feet.

Without planning, everything is new to you when you encounter it, like the side of the bowl to a goldfish. You receive no benefit from history and other people’s experience. You likely have no sense of whether your key assumptions are reasonable. You might not even know that your plan relies upon a host of implicit assumptions, since you haven’t asked the question.

On the other hand, even the most carefully considered plans can’t anticipate everything in the world, where conditions continually evolve. It would be foolish to walk over a cliff while staring at your map, insisting that the map shows no cliff.

Especially with plans that need lots of time to unfold, like investment plans, it’s important to harness the combination of both planning and trial and error. If you haven’t examined the historical returns of different investment strategies, it’s hard to have any reasonable expectation for how much return you might earn or any sense of how much risk you can afford to take. If you haven’t studied past bear markets, the current one can look like the end of the world.

A sound investment process considers these issues and makes the best decisions possible given all available information. But it also explicitly acknowledges that conditions will change, and new information may require reassessment once you’ve implemented your plan. The plan thus continually rolls forward in a continuous cycle of reflection, execution, and assessment in order to strike the proper balance between making considered decisions and improvising when necessary.

This is a stronger approach than continually “figuring things out” all along the way, since you already have a framework to assist with your analysis and are less likely to make decisions that are, at heart, merely reactions to whatever is happening at that moment.

None of this seems controversial, so why does planning get such a bad rap? If you want to make God laugh, the saying goes, tell her your plans. Boxer Mike Tyson famously observed that “everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.”

One reason is that many plans are wildly optimistic stories about what we’d like to see happen. Aim high, we’re told, so we wish for everything on the list, as soon as possible, and we use the planning process as a means of persuading ourselves that the goals we want to accomplish really can, no will happen. The renovation will come in under budget; the new product will launch months early; our portfolio values will double in five years.

Behavioral psychologists call our propensity to be too optimistic the “planning fallacy,” and research suggests this bias is biologically hardwired into many people. It’s an unfortunate label, because such “plans” are more “wishes” than anything else.

Another reason for the animosity towards plans is we ask too much of them. We use them not as tools for making decisions in the face of uncertainty, but as an attempt to squeeze all the uncertainty out of the future.

As the authors of “Designing Your Life,” a book we discussed earlier (What If You Could Test Drive Your Life?), note:

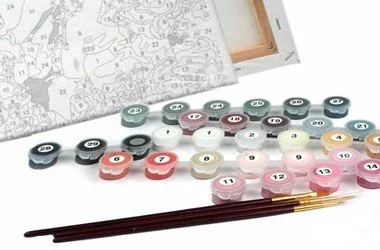

Working with adults of all ages, we’ve found that where people go wrong (regardless of their age, education, or career path) is thinking they just need to come up with a plan for their lives and it will be smooth sailing. If only they make the right choice (the best, true, only choice), they will have a blueprint for who they will be, what they will do, and how they will live. It’s a paint-by-numbers approach to life, but in reality, life is more of an abstract painting - one that’s open to multiple interpretations. (p. 87)

Remaining “open to interpretation” is a good way to describe how Lucas Congdon approached his blueprints. They were a good first stab at what needed to happen to complete a tropical oasis with plants, recessed lighting, and adjacent bar and grill, but not a detailed prescription for every step along the way.

By contrast, we can see the ills of paint-by-number approaches to goals among disgruntled doctors, lawyers, and computer engineers who decided to “play it safe” with their careers, rather than explore other options. Many college students, often at the insistence of the colleges themselves, lock in their major before they set foot on campus, shutting down curiosity about other fields of study they might pursue. It’s no surprise that a shockingly high proportion of college graduates wished they’d studied something else. Nearly half of people who choose these college majors regret it, federal survey finds

Few lives can be reduced to fit neatly into a box with predetermined materials and a marketing slogan like “Every Man a Rembrandt!” If nothing else, as people seemed to understand better in earlier times than ours, the role of chance in life can swamp everything else.

Recently, an Italian team of two physicists and an economist ran a mathematical experiment to prove the somewhat depressing hypothesis that “having average talent but ample luck is better than lots of talent and little luck. And the most successful people in their simulations were the ones with moderate talent and magnificent luck.” (Winners Know How To Harness Luck WSJ Oct 8, 2022)

More optimistically, they noted that there was a way that “people can make their own luck, if they’re willing to

expose, explore, exploit. Try a bunch of things. Find out what you like, and figure out what you’re good at. Then focus your talents and get to work. That’s how you can take advantage if the world evolves your way.

It’s an argument for trial and error, but a good plan can assist and accelerate the process, helping to develop the most promising hypotheses that you can then go test in the field. Looking at plans as repeated experiments from which you learn and improve rather than as predictions for how your life ought to proceed will mean less disappointment. It might also increase the opportunities for luck to land in your favor.